Sea Ice

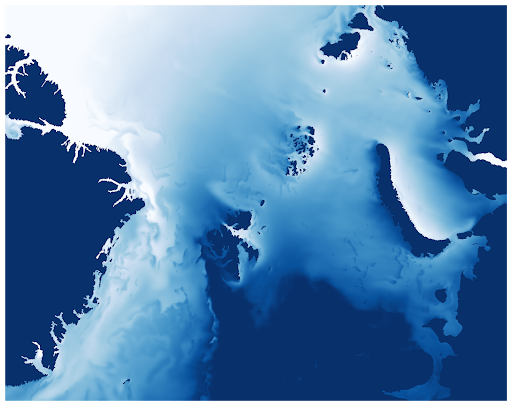

Figure: Snapshot of Arctic sea ice thickness (Greenland, Barents and Kara Seas) from a CM4 simulation (⅛-degree ocean and sea ice). The Fram strait (between Greenland and Svalbard) exports approximately 10% of the total Northern Hemisphere sea ice cover out of the Arctic basin annually.

Sea ice is the thin layer of frozen ocean that exists at the high latitudes, forming when ocean temperatures are sufficiently cooled by the atmosphere. It plays a major role in the Earth’s climate and ecosystems, reflecting incoming solar radiation to keep surface temperatures cool, regulating large-scale ocean currents through the re-circulation of salt and nutrients, providing an integral platform for connecting Arctic communities, and also a natural habitat for endemic species. Sea ice loss due to anthropogenic climate change is posing a threat to the balance of these various human and natural systems. Over the past decade for example, the average summer Arctic sea ice cover was more than 60% lower than in the 1980s.The importance of sea ice in the climate system was illustrated in the seminal works of Manabe & Stouffer in 1980, who showed that, due to positive ice-albedo feedbacks, the dominant climate response to quadrupling CO₂ is the seasonal loss of the Arctic sea ice cover. Even before this however there had been concerted efforts to understand and model the physical processes that control sea ice evolution – efforts which would subsequently lay the foundations for nearly all sea ice models over the next 4-5 decades! For example, all of the latest-generation (CMIP6) climate models still use the ice thickness distribution formulation devised by Thorndike in 1975, as well as some variation of the viscous-plastic sea ice rheology scheme developed by Hibler in 1979. Since the 1970s however, there have been several important sea ice physics developments, including: an energy-conserving model for sea ice thermodynamics (Bitz & Lipscombe, 1999), the incorporation of multiple scattering sea ice radiative transfer (Briegleb and Light 2007; Holland et al 2012), the formulation for sea ice surface melt ponds (Flocco et al 2012; Hunke et al 2013), and also recent work on sea ice rheology to better represent damage mechanics (Maxwell Elasto-Brittle rheology; Dansereau et al., 2016).

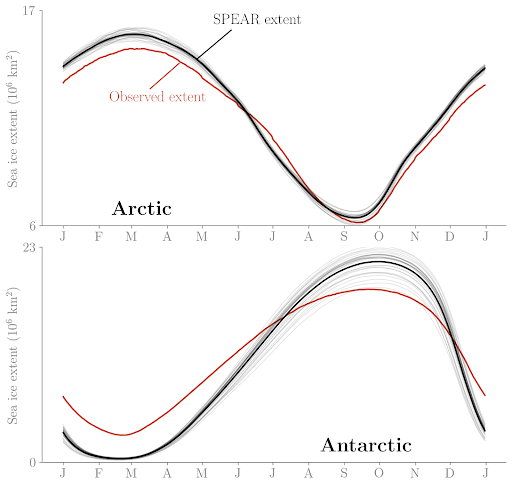

Although sea ice models are continuously improving, there is still work to do. We can see this in the figure below, which shows the sea ice extent climatology of the GFDL SPEAR (1-degree) climate model in both the Arctic and Antarctic. Here we see that SPEAR generally has a good representation of the total Arctic sea ice cover. On the other hand, SPEAR’s Antarctic biases are more severe, with too little sea ice across the summer–fall seasons, and then too much sea ice in winter.

Figure: Sea ice mean state (1979-2010) of the GFDL SPEAR large ensemble (historical simulation). Thin grey lines represent individual ensemble members and the black line is the ensemble mean. Shown for (top) Arctic, (bottom) Antarctic.

Biases in the sea ice mean state are due to a myriad of factors, and are often difficult to isolate. Biases may originate from missing physics within the sea ice model itself (e.g., absence of a sea ice ridging scheme), or from errors in sea ice model parameters (e.g., sea ice albedo or snow thermal conductivity). Furthermore sea ice is strongly coupled to the atmosphere and ocean, hence biases in either one of these components can imprint on the sea ice.M²LInES is working to improve sea ice model biases by developing new data-driven sea ice model parameterization schemes. Recent highlights include work from M²LInES members Lorenzo Zampieri and Marika Holland, who used in-situ data from the recent MOSAiC expedition ( Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate) to derive a new parametric correction to sea ice and snow conductive heat fluxes within the CICE sea ice model. This work showed that simulations which do not account for local-scale sea ice and snow heterogeneity can under-estimate conductive heat fluxes through sea ice by up to 10% (see this work in GRL).

Additional work by Will Gregory and Mitch Bushuk has shown that data assimilation can be used to extract the systematic component of sea ice model error within sub-grid model state variables, and subsequently that neural networks can learn this error very effectively (see work in JAMES). In follow-up work they showed that this neural network can be used to bias-correct sea ice conditions during online global ice-ocean simulations (see work in GRL), and outlined how this framework of data assimilation + machine learning can also be used to improve online generalization of machine learning models.